Why Benedict Anderson Wrote That the Nation Is an "Imagined Community"

In his 1983 work, Benedict Anderson argues that the nation is not a primordial entity but a socially constructed phenomenon, an imagined community.

Antonis Chaliakopoulos

Antonis is an archaeologist with a passion for museums and heritage and a keen interest in aesthetics and the reception of classical art. He holds an MSc in Museum Studies from the University of Glasgow and a BA in History and Archaeology from the University of Athens (NKUA), where he is currently working on his PhD.

Summary

- Definition: Anderson defines the nation as an "imagined community" because members will never meet most of their fellows, yet they share a mental image of their communion.

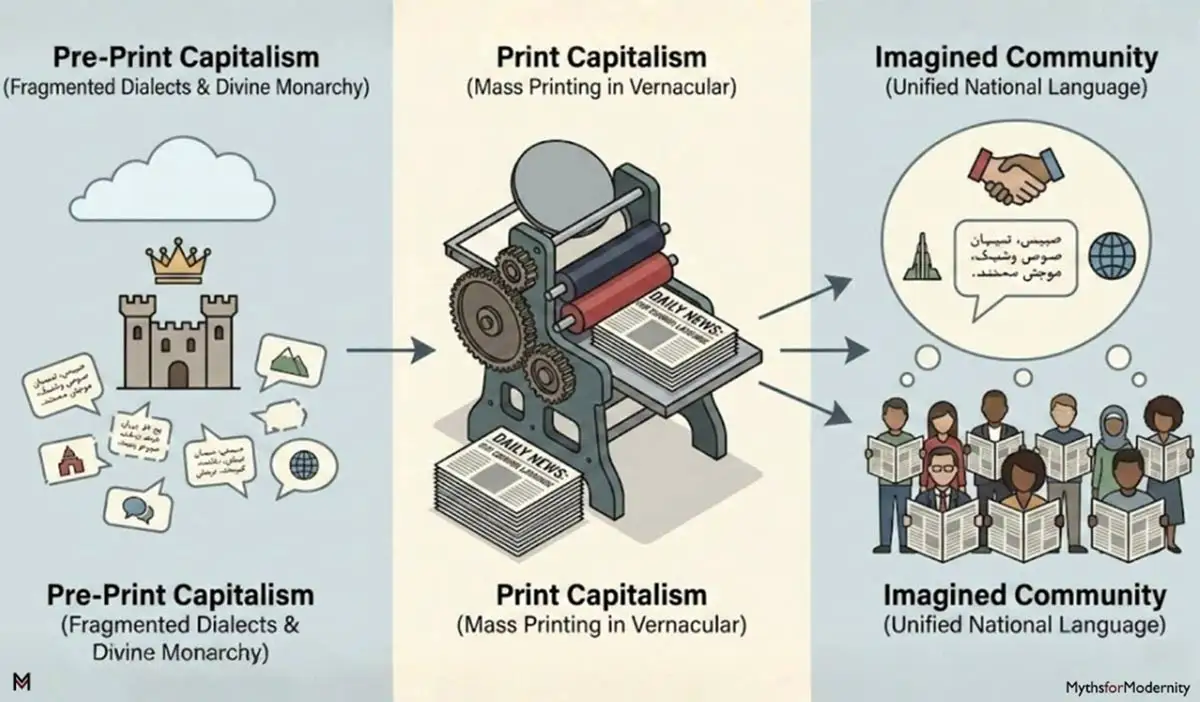

- Print Capitalism: The primary engine behind the rise of nationalism was "print capitalism." The mass production of books and newspapers in the vernacular (common language) allowed disparate groups to communicate and see themselves as part of a single, unified discourse.

- A Modern Construct: Contrary to theories suggesting nations have ancient roots, Anderson places the nation’s birth during the Industrial Revolution.

In his landmark "Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism" (1983), the Anglo-Irish historian Benedict Anderson claimed that the nation is an imagined community.

But what did he mean by that term?

A Modernist Understanding of the Nation

In his work, Benedict Anderson studied nationalism across time and space and came to the conclusion that the nation is not a naturally occurring phenomenon, but a socially constructed "imagined community."

This is a position he shared with other theorists of modernism (such as Hobsbawm). Later movements that critiqued modernism, such as Anthony D. Smith's ethnosymbolism, agreed with Anderson that the nation is a modern construct but argued that it is based on prior "ethnic" roots.

The Three Core Traits of an Imagined Community

According to Anderson, every nation shares three fundamental characteristics:

- Limited: Even the largest nation has finite, if elastic, boundaries. It does not encompass all of humanity; it ends where another nation begins.

- Sovereign: The concept emerged during the Enlightenment, replacing the idea of "divinely-ordained" monarchies. The nation is the ultimate authority over itself.

- Community: Regardless of actual inequality or exploitation, the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship.

Anderson looked at the processes that took place on the onset of the Industrial Revolution, specifically the decline of divine, Medieval-like monarchies (think of the Holy Roman Empire) and the emergence of what he called "print capitalism". The last one is particularly important.

Print Capitalism

Benedict used the term "print capitalism" to describe a capitalist market that shapes a common language and discourse through the mass printing and distribution of the press in the vernacular (ordinary spoken language) to maximize its reach. This way, print capitalism shapes a community able to understand a commonly accepted version of the vernacular and not one divided by a multitude of dialects.

So, Why Is the Nation "Imagined?

Anderson answers the questions in simple terms:

"is imagined, because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet, in the minds of each lives the image of their communion."

And Why Is It a "Community"?

Because for those who participate in it, "the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship."

It is exactly this idea of comradeship that makes it possible for someone to give their life to protect someone they have never met, and it is exactly that which, according to Anderson, makes the nation so persistent.

The Nation as an Imagined Community

According to Anderson, the nation emerged recently and is both limited, in that it has limits, and sovereign, in that no single monarch can claim the nation for themselves, as happened in the past.

Anderson describes beautifully how the imagined community of the nation takes shape as one reads the news in the newspaper:

"It is performed in silent privacy [the reading of the paper], in the lair of the skull. Yet each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion."

Further Reading

- Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

- Gellner, E. (1983). Nations and Nationalism. Cornell University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. J., & Ranger, T. (Eds.). (1983). The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, A. D. (1986). The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Blackwell.