A Deep Dive Into Freud’s Uncanny (From Greek Mythology to Slenderman)

From ancient Greek myths of living statues to the modern anxiety of the Uncanny Valley and AI, explore why the familiar feels so frightening.

Antonis Chaliakopoulos

Antonis is an archaeologist with a passion for museums and heritage and a keen interest in aesthetics and the reception of classical art. He holds an MSc in Museum Studies from the University of Glasgow and a BA in History and Archaeology from the University of Athens (NKUA), where he is currently working on his PhD.

Summary

- Freud defined the Uncanny (Das Unheimliche) not just as the 'scary,' but as the frightening that leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.

- Freud's essay references multiple uncanny stories from Greek mythology.

- From Mori's "Uncanny Valley" to social media, technology continues to fuel discussions about uncanny experiences

In his landmark 1919 essay Das Unheimliche, Sigmund Freud outlined the psychological concept of that which is familiar yet different in a way that evokes horror. The term became known in English as "the uncanny" and is one of Freud's rare, yet valuable, explorations into the field of the philosophy of art.

Uncanny vs. Unheimlich

In 2024, I interviewed renowned psychoanalyst and neuropsychologist Dr. Mark Solms to talk about his translation of Sigmund Freud’s complete psychological works published by the Institute of Psychoanalysis and publishers Bloomsbury. Talking about the uncanny, Solms noted that even though the term is usually translated as "uncanny", it does not capture the concept's essence as the the original German "unheimlich" does.

In German, heimlich literally means something that is homely, familiar, comfortably nostalgic or reminiscent of one's childhood. Unheimlich should mean the exact opposite, something unhomely, unfamiliar, something not comfortably nostalgic or reminiscent of one's childhood. However, as used by Freud, the unheimlich conveys neither the homely, nor the unhomely, but rather a union of the two, something unfamiliar within the familiar that evokes horror.

You may also enjoy reading our article on how societies shape their collective memory.

Freud's 1919 Essay on the Uncanny

In his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche, Freud situates the uncanny within the realm of the scary:

"It undoubtedly belongs to all that is terrible—to all that arouses dread and creeping horror..."

However, it has a unique quality that differentiates it from things that are simply scary. In his words, "the “uncanny” is that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar."

As Solms explained in the previous section, Freud understood the unheimlich as a subclass of the heimlich that is turning against itself, a concept which might seem strange, but perfectly explains why the home, our most familiar environment, can be such an effective setting for a horror movie.

Three Aspects of the Uncanny

Freud goes into great detail describing various uncanny experiences drawn from literature and real life. We can group them into three major categories:

- meeting your double (doppelgänger) or stories involving twins, things that look the same, but are not.

- inanimate objects that look (and may become) alive, such as shadows, dolls, or automata (robots). Here we could include dead bodies that return to life, and body parts.

- Involuntary repetition (e.g. encountering the same number multiple times in the same day) or involuntary return to the same place (e.g. someone getting lost in the woods arriving at a familiar clearing). What is common in these experiences is that they create a sense of helplessness.

Freud's Uncanny Walk in Italy

Freud also shares a personal uncanny experience from a time he got lost in an Italian town which I quote below:

Once, as I was walking through the deserted streets of a provincial town in Italy which was strange to me, on a hot summer afternoon, I found myself in a quarter the character of which could not long remain in doubt. Nothing but painted women were to be seen at the windows of the small houses, and I hastened to leave the narrow street at the next turning. But after having wandered about for a while without being directed, I suddenly found myself back in the same street, where my presence was now beginning to excite attention. I hurried away once more, but only to arrive yet a third time by devious paths in the same place. Now, however, a feeling overcame me which I can only describe as uncanny, and I was glad enough to abandon my exploratory walk and get straight back to the piazza I had left a short while before.

Causes

Toward the end of his essay, Freud summarizes the causes of the uncanny, though he seems to believe that all the causes stem from the last one on the list, i.e. the castration-complex. As Mark Fisher (2016) has noted, the idea that the fear of castration is behind the uncanny is a frustrating belief but does not affect Freud's observations on the nature of the uncanny.

Here are the causes listed by Freud:

- animism: the belief that the world is inhabited by spirits.

- magic and witchcraft: the belief system and the set of practices that attempt to tame or make contact with the supernatural.

- the omnipotence of thoughts: the idea that one's thoughts have real consequences on the material world (such as killing someone by simply wishing to do so).

- attitude to death: the deeply-rooted fear of death and the fact that it remains a mystery.

- involuntary repetition: an example is meeting someone named Steve in the morning and receiving a phone call from someone else named Steve in the evening or encountering the number 16 multiple times in one day.

- the castration-complex: the fear of castration (or having already been castrated) that arises during the psychosexual development of the child in Freudian theory.

The Evil Eye and the Medusa

Freud describes how the superstition of the evil eye can be understood as uncanny:

"One of the most uncanny and wide-spread forms of superstition is the dread of the evil eye[ ...]Whoever possesses something at once valuable and fragile is afraid of the envy of others, in that he projects on to them the envy he would have felt in their place [...]What is feared is thus a secret intention of harming someone, and certain signs are taken to mean that such an intention is capable of becoming an act."

What is the evil eye? The belief that someone's malicious gaze can cause harm. In the ancient Mediterranean World, this belief took a mythical form in the face of the Medusa, a being whose eyes could petrify those looking directly at them. In Greece and Rome, Medusa's eyes were widely used as symbols of protection against evil spirits. In a sense, using Medusa's eyes to fight against the evil eye or other spirits was sort of a "fight fire with fire" practice that also allowed for Medusa, a symbol of horror, to be tamed.

A descendant of Medusa's eyes is the so-called evil-eye trinkets that can be found all over the Mediterrenean World with similar properties (protection against evil).

You can also read Freud's essay on Medusa as an example of the fear of castration or this article I wrote a few years ago about Medusa's symbolism in antiquity.

Freud situates the evil eye superstition within "the omnipotence of thoughts", i.e. the idea that one's thoughts have real consequences on the material world, which is also a concept closely tied to animism, the belief that the world is inhabited by spirits. For the psychologist, the uncanny is but a trace of the feelings that humans would have experienced in premodern times, when their world was enmeshed in animism, back when malevolent spirits could hide in wild rivers and dark forests. Of course, things are more complex than Freud would have liked, as animism never really left us, but that is a topic for another blog.

Uncanny Stories from Greek Mythology

Freud provides multiple examples of uncanny ancient myths.

- Narcissus: The myth of Narcissus is a prime example of the uncanny feeling evoked by "doubles". Narcissus fell in love with his own idol as reflected in a pool of water.

- Automata: Freud mentions the term automaton to describe a self-moving machine (robot as a term was popularized later in the 20th century).The term automaton comes from ancient Greek and literally translates to "that which moves of its own volition". A famous mythical automaton was the bronze giant Talus, created by the god Hephaestus to protect Crete from invaders.

Other myths that are not mentioned in Freud's essay but are closely linked to the uncanny:

- Pygmalion: A prime example of a myth where an inanimate human-like object (like a doll) becomes alive. In the story, Pygmalion sculpts a marble image of the perfect woman and falls in love with it. Aphrodite eventually breathes life into the statue which marries its creator.

- Daedalus: The legendary sculptor-architect-inventor (sort of like an ancient Da Vinci or Tony Stark) was said to create statues that could move or even run away if not tied down. He also created the labyrinth, arguably, the most uncanny of architectural forms.

- Minotaur: The Minotaur's birth is a true uncanny tale. The Minotaur, a beast half man and half bull, was born after Pasiphae, the Queen of Crete, was cursed to fall in love and mate with a bull.

Throughout his work, notably in Totem and Taboo (1913), Freud sought to "read" myths as products of various psychological workings linked to the unconscious. Of course, Freud's is just a way to percieve the world of mythology, just an approach, not the whole image.

The Greeks, just as the peoples before and around them, told uncanny stories of strange anthropomorphic (human-like) beings, notably centaurs (human's head with a horse's body) and satyrs (human head with goat or horse legs and ears). These tales often featured supernatural transformations, of human turning into everything imaginable, from animals to constellations and all sorts of inanimate objects. The opposite, an inanimate object becoming alive, was also possible, as a cold piece of marble could turn into "the perfect woman" in Pygmalion's case, or a cloud could take the form of a goddess in Ixion's case.

These stories can all be approached as ways to explore the natural world and to make sense of a wild, unknown universe that at times felt uncanny and strange.

The Ring of Polycrates

Freud also mentions the story of Polycrates. The tale is told in the third book of Herodotus (3.40-42) and concerns Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, who had an extremely good fortune. Amasis, the king of Egypt, told Polycrates that his life was too good to end well and that he should throw away whatever he cared for the most in order to appease his fortune.

Polycrates heard Amasis' advice and threw his ring in the sea. Later, a fisherman caught a fish that had eaten the ring, which eventually made its way back to Polycrates. Amasis learned of the event and broke his alliance with Polycrates believing that such good luck would eventually turn into grave misfortune.

The hand in the story of Rhampsinit is also mentioned in Freud's essay. In Herodotus' second book (2.121-124) appears the story of the fictitious Egyptian pharaoh named Rhampsinit. At some point in the story, a thief who has stolen Rhampsinit's gold, uses the hand of his dead brother as an unexpected "prop" to avoid capture. Freud treats this story as a case where a human part (a hand) is used in a way that is not uncanny because the story focuses on the thief's cunning and not the point of view of those seeing the hand.

In Surrealism

After Freud's essay was published, artists kept returning to it looking for inspiration. Alongside other Freudian concepts such as the unconscious and its manifestation in dreams, the uncanny proved particularly influential among the Surrealists who sought to uncover unconscious thoughts through and within art, often employing elements drawn from myth.

Noteworthy examples of Surrealist art featuring retellings of Greek myths in an uncanny way include Dali's interpretation of the myth of Narcissus and Leonora Carrington's strange Minotaur (see above image).

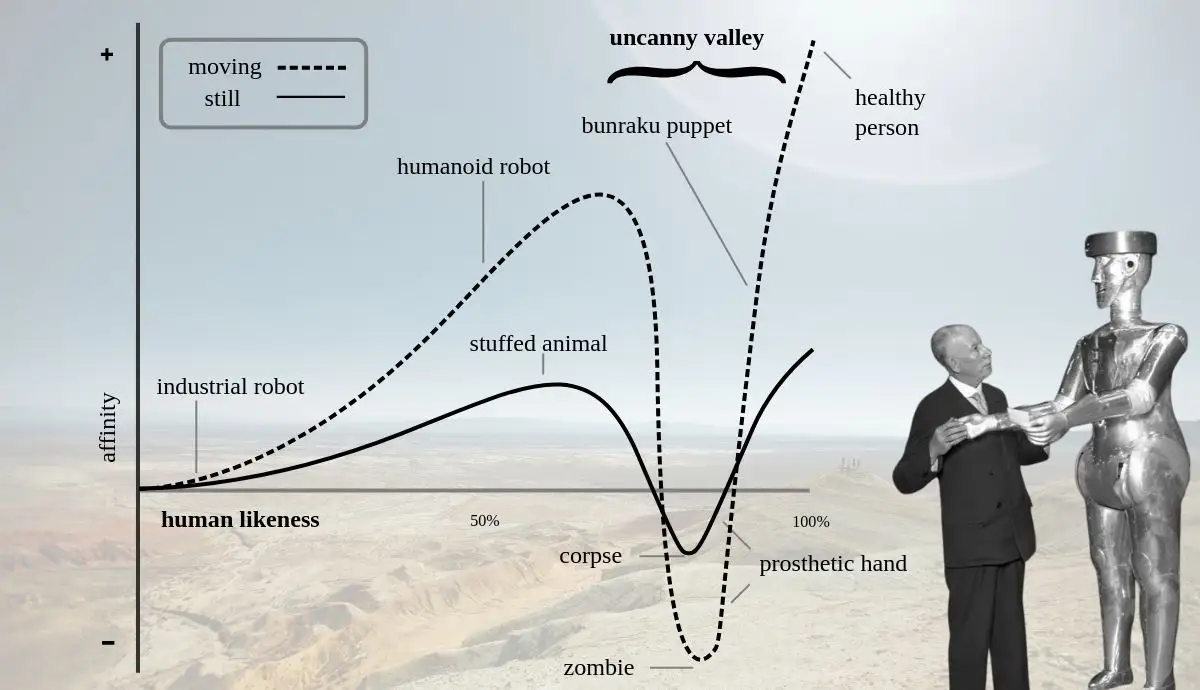

The Uncanny Valley

In 1970, robotics professor Masahiro Mori wrote an article on what he described as "the Uncanny Valley". Mori claimed that as robots become more and more human-like our attitude towards them changes.

A robotic arm in a factory is not likeable at all but a robot that looks a bit more like a human, like R2D2 from Star Wars or Disney's Wall-E, is ok or even funny. However, as soon as a robot becomes more human, it begins to evoke eerie/uncanny responses. As the robot gets more and more humanlike, the uncanny feelings become more and more intense. However, at a fully anthropomorphic state the response becomes positive once more. Mori advises his fellow roboticists that it is better to opt for a humanoid that is not too human so as to avoid falling inside the uncanny valley as a fully anthropomorphic state is extremely difficult to achieve. Instead he proposes going for the first peak, for robots with a few anthropomorphic features that keep them distinctly "robotic".

Mori's essay does not explain why humanoids feel scary but it does help us understand why we get uneasy watching a deepfake, why AI-generated videos about dancing squirrels can make us laugh, but realistic AI-videos can give us the creeps.

Man, the Internet Is So Uncanny...

In an increasingly digital world of rapid technological innovation, we are putting Mori's theory to the test every day.

Avatars on Facebook and Instagram may not be anyone's favorite yet, but the more human-like they become, the more they look and feel like our digital doubles. Will we eventually fall in love with them too, just like Narcissus with his idol? We have certainly become obsessed with our social media personae, which, arguably, function less like our doppelgänger and more like digital manifestations of our Superego.

Then we return to robots and AI-generated videos. How human is too human or is it just a matter of getting the human right, as Mori seems to have claimed? Even talking to ChatGPT and Gemini can feel uncanny at times, though we are getting used to that; possibly more than we should.

The world is getting stranger, as animism is making an unexpected return in the form of the cloud, a digital spirit that feels at once ever-present and all-knowing. Our real world is about to merge with the digital in unprecedented ways with AI agents and chatbots getting ready to "inhabit" everything from our car to our phone and from our toaster to our mirror. The world is getting more and more uncanny as it is exploring Mori's deepest valleys.

Perhaps that's why new mythologies are springing up about haunted liminal spaces on the web (abandoned forums, chatrooms with strange users, etc), deadly creepypastas (see Slenderman), or the dead internet theory, and the fear that humanity's digital doppelgänger (some sort of AI superintelligence) will eventually haunt and destroy the world.

Then again, perhaps, uncanny feelings are part of the human experience. No matter the time or place, as long as there is the familiar, there will be the uncanny.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between the uncanny and the weird?

In his The Weird and the Eerie (2016), Mark Fisher separates Freud's uncanny from the eerie and the weird. For Fisher, the uncanny is about the unfamiliar inside the familiar, but the weird and the eerie capture a different sort of strange. They are about experiencing the inside (the familiar) from the outside (from an unfamiliar perspective).

What is a heterotopia? Is it similar to the uncanny?

Michel Foucault's heterotopia refers to a space (like mental institutions or prisons) that constitutes something "other" that exists in contradiction to social norms. Heterotopias function as "worlds within worlds", they are within and at the same time outside of society. Foucault first wrote about the term in The Order of Things (1966).

Heterotopias do not invoke fear, as the uncanny. However there is some common ground in the way that they both embody something familiar in an unfamiliar way. For example, in a prison everyone has to act according to the strictest societal expectations (wake up early, eat at set times, sleep during standard hours, etc) but in a way that is under no circumstances "normal".

Bibliography

- Freud, Sigmund. 1919. The Uncanny. Translated by Alix Strachey.

- Fisher, Mark. 2016. The Weird and the Eerie. Repeater Books.

- Mori, Mashahiro. 1970. The Uncanny Valley. Energy, 7(4), pp. 33-35. Translated by Karl F. MacDorman and Takashi Minato.

Also read our article on how nationalism adopts symbols and myths to foster a common identity.