The Ship as a Transnational Arena: An Interview with Historian Argyris Sakorafas

PhD candidate Argyris Sakorafas discusses the experience of Greek migrants on the transatlantic journey and why steamships were true global melting pots.

Antonis Chaliakopoulos

Antonis is an archaeologist with a passion for museums and heritage and a keen interest in aesthetics and the reception of classical art. He holds an MSc in Museum Studies from the University of Glasgow and a BA in History and Archaeology from the University of Athens (NKUA), where he is currently working on his PhD.

Key Takeaways

- The Ship as a "Transnational Arena": The ship acted as a "transnational" space where diverse cultures, languages, and religions interacted.

- Human Agency: Argyris' research seeks to balance a historical approach with the personal sides of migration, such as those of the "picture brides" who traveled with only a photograph of their future husbands, and the objective.

- The Challenge of Dispersed Archives: Reconstructing the personal histories behind these transatlantic migrations, is a complex puzzle because archives moved with the people, leaving records scattered across international institutions or forgotten in private family collections.

What happens in the "in-between" spaces of history? While many historians focus on why migrants left and where they arrived, Argyris Sakorafas, PhD candidate at Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf and member of the ERC-funded MEDMACH project, is looking at the journey itself.

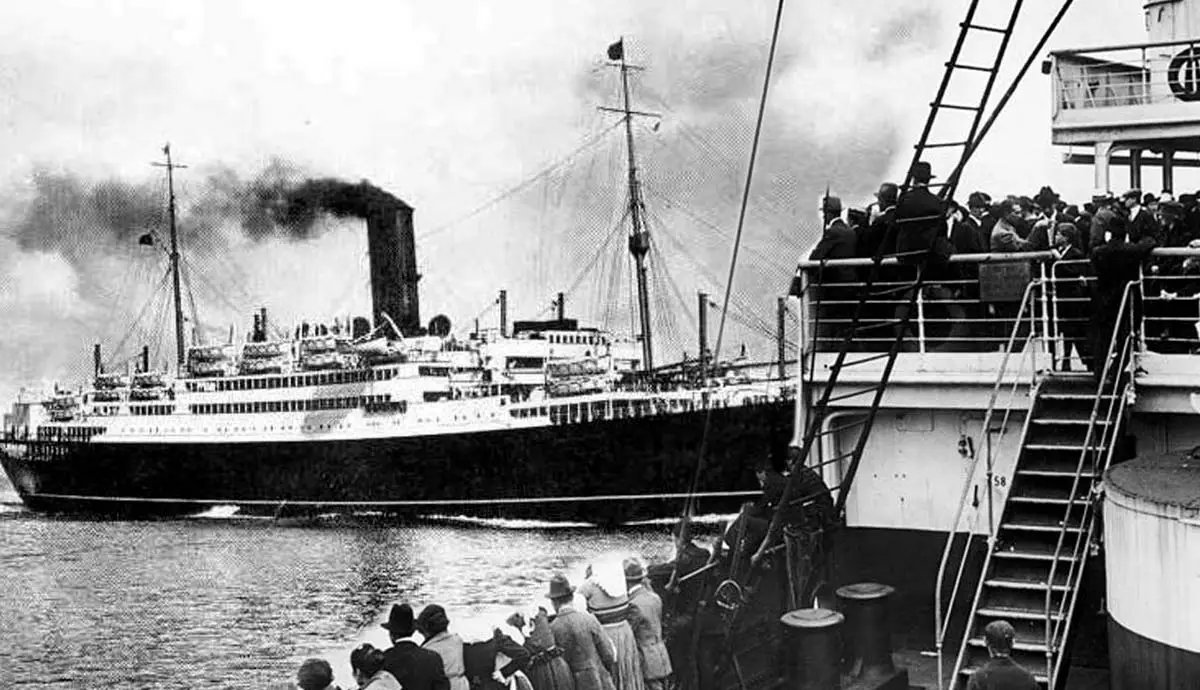

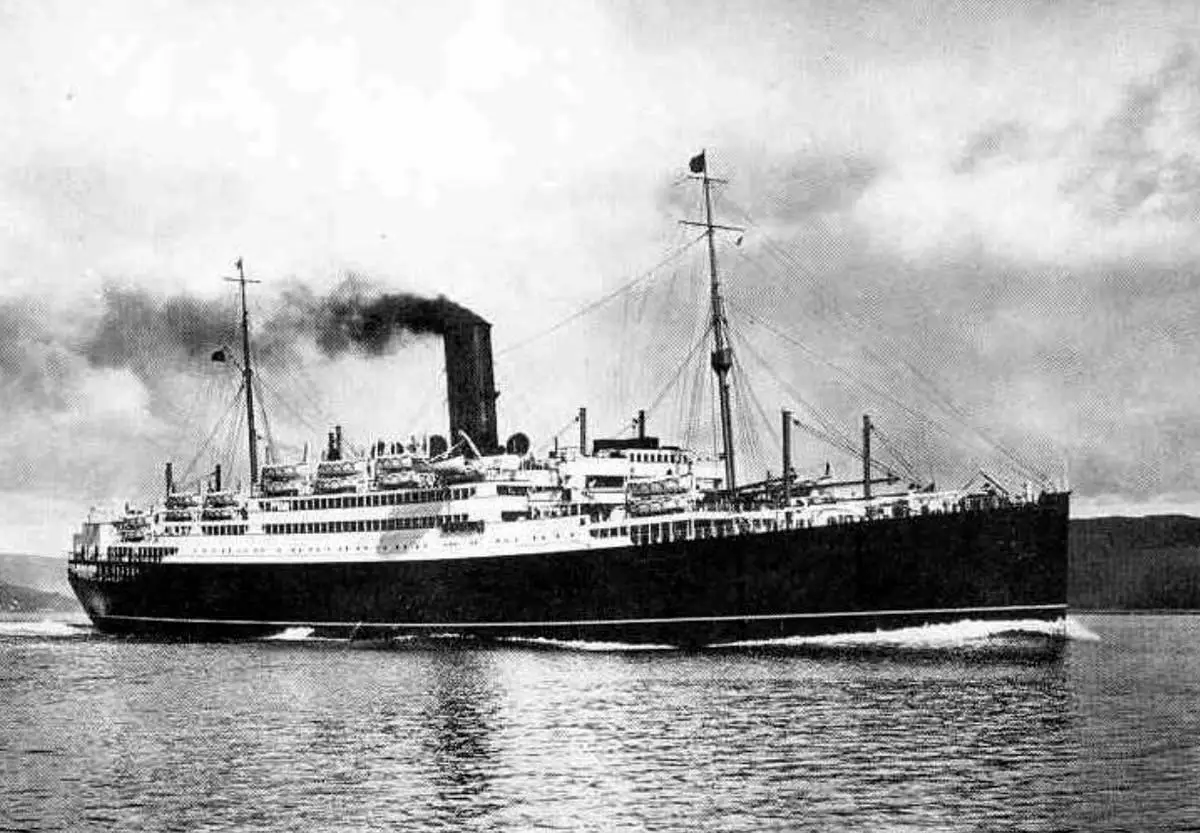

Argyris' research focuses mainly on the experience of Greeks migrating to America in the 20th century. As these migrants embarked on the long transatlantic journey to the New World, they transformed the ship into a "transnational arena", a unique space where cultures collided and coalesced.

In this interview, we will look into some little-known aspects of Mediterranean migration, such as "picture brides" and the things that made ships true global melting pots.

From Family Roots to Global History

Q: Why did you select this specific topic for your PhD? Why ships in particular?

Argyris Sakorafas: Ships have always sparked historians’ interest, and they still continue to fascinate scholars across various fields. While focusing on shipping history, historians also studied the places of departure and arrival, investigating the role of ports as hubs of entanglement, whether for the movement of people, trade, slavery or colonial expansion, with the ship acting as the main connector.

The passage, however, has often been overlooked, despite the nature of the journey, which required people from diverse backgrounds to spend weeks in a confined space, entirely detached from the outside world. This observation, combined with impulses from my studies in Global History and a family history, were the main reasons behind the development of my research proposal.

📜 You may also enjoy reading our article on Benedict Anderson's theory on nationalism, where we discuss how the concept of the nation was born through Print Capitalism during the Industrial Revolution

Q: Does your family have a history of migration through these Mediterranean ports?

Argyris: Like many Greeks with roots in the Peloponnese, my family also had members who crossed the saltwater curtain of the Atlantic in the early twentieth century. One such story was the inspiration for my research: it is the story of my grandfather’s sister, a young girl who travelled from Greece to Argentina after an arranged marriage, carrying just a photograph of her future husband, what was often called a “picture bride”.

Although I was not able to trace more on this specific story, it provided the initial spark to look deeper into the social, experiential and transnational aspects of the journey.

The Ship as a "Transnational Arena"

Q: Why do you describe the ship as a “transnational arena”?

Argyris: First, we need to define what “transnational” means. As recent historical studies have demonstrated, transnational history focuses on how people, objects and ideas move across nations and geographical boundaries. To do so, it moves beyond national borders and historiographies. In addition, transnational history identifies the significance of studying in-between people and spaces. Essentially, this is the nature both of the migrants and the ship.

The migrants, during their journey but also after their arrival, are standing between their homeland and their new life. On the other hand, the ship is a confined place where different religions, languages and cultures interact and clash, forming connections but also disconnections.

“The ship is a confined place where different religions, languages, and cultures interact and clash, forming connections but also disconnections.”

Discoveries in the MEDMACH Archives

Q: Through your work with the MEDMACH project, what is the most surprising visual detail you’ve found in the archives?

Argyris: While looking into a migrant’s personal collection, I found a postcard of the Pont Transbordeur, an emblematic transporter bridge and a landmark of Marseille, which is the case study of one of my colleagues in the project. Initially, I wasn’t sure why this postcard was in his collection. After doing some research, I found out that this person transited through Marseille to reach the port of Boulogne via railway before crossing the Atlantic.

Until then, I thought our case studies were completely unconnected. This is when I realized that to study the history of migration in the early twentieth century, one needs to consider the broader transnational developments in infrastructure, economy and society.

📜 You may also enjoy reading our article on Anthony D. Smith's ethnosymbolism, where we discuss how nationalism employs cultural resources drawn from pre-existing ethnic communities.

The Human Element: Staying Objective vs. Feeling Connected

Q: When you’re deep in the records, do you ever feel like you "know" these passengers?

Argyris: A historian’s role is to be objective, maintaining a distance from the subject of his research. However, when personal stories become the subject of investigation, this thin line is often crossed. Here, a historian must be sure not to be biased and jump to conclusions that fit their imagined narrative. This can be particularly evident when studying migration from a human agency perspective, as historians may feel connected to a personal story.

Q: Is there one person’s story that keeps you up at night?

Argyris: I do have such a story: it’s the case of a young migrant who migrated to Mexico in 1924. His brothers had already migrated to Chicago but due to immigration restrictions imposed in the United States, he eventually stayed in Mexico. His personal correspondence with his brothers and relatives in Greece reveals the constant attempts of the family to reunite either in the United States or Greece. Nevertheless, they remained apart until death, with their letters showing the sorrow and negative aspects of migration.

Q: In an era before digital distractions, how did thousands of people kill time during a two-week Atlantic crossing?

Argyris: That’s a good point that many people often forget. Nowadays, travelling is almost always combined with watching a movie, playing mobile games or browsing. Sources tell us that the main entertainment during the transatlantic crossing was human interaction. In both upper and lower decks, people were engaged in board games, dances and music.

Passengers write about their vivid conversations with people from different countries and regions, their encounters with the other. Reading books or writing poems and diaries was also common. Naturally, even the entertainment aspect demonstrates the social hierarchies formed aboard and the different amenities between migrants and first-class passengers.

"Understanding past migration is essential to interpret not only why these people left their homes but also how contemporary governments shape policies and how modern societies interact with them."

Q: If you could go back in time for just one hour, would you rather sit in the first-class dining saloon or talk to a stoker in the furnace room?

Argyris: That’s a tricky question. Both passenger types would have important experiences to share. I would ideally choose to be a crew member. These people had access to both first and third-class (steerage) spaces. Hence, I would be able to see the daily routine in both decks and better understand the dynamics formed inside the ocean liner.

The Challenge of Modern Memory

Q: Why is it important to remember these stories of migration today?

Argyris: A migration historian once said that migration studies are always relevant because migration is a perpetual phenomenon. One needs to think of prehistoric migrations and, of course, contemporary migration waves in the Mediterranean and elsewhere. Understanding past migration is essential to interpret not only why these people left their homes but also how contemporary governments shape policies and how modern societies interact with them.

Q: What, in your opinion, is the greatest challenge of your project?

Argyris: Tracing the archives is clearly the biggest challenge. The early twentieth century was a period of unprecedented mobility, taking into consideration developments in steam technology. The movement of people across continents meant that archives were moving with them; as such, archives of transatlantic migration are dispersed in several smaller and larger institutions in Europe and the Americas. Moreover, in most cases, personal migrant material is still in their families’ collection, possibly stored and forgotten somewhere in the attic. Therefore, to trace such material, a researcher has to conduct deep, often exhaustive but eventually highly rewarding research.