The Social Role of Memory in the Work of Herodotus

Herodotus described his role as a historian as a twofold struggle against the “lapse of time” and “forgetting”.

Antonis Chaliakopoulos

Antonis is an archaeologist with a passion for museums and heritage and a keen interest in aesthetics and the reception of classical art. He holds an MSc in Museum Studies from the University of Glasgow and a BA in History and Archaeology from the University of Athens (NKUA), where he is currently working on his PhD.

| Key Takeaways |

| - Communicative memory (oral memory) usually fades within three generations, requiring cultural memory (texts/images/rituals) for long-term survival. |

| - By writing the Histories, Herodotus "crystallized" fading oral testimonies into a permanent record. |

| - Ancient Greeks viewed forgetting as a "second death." Recording history ensures kleos (good fame) for the heroes described and the historian himself. |

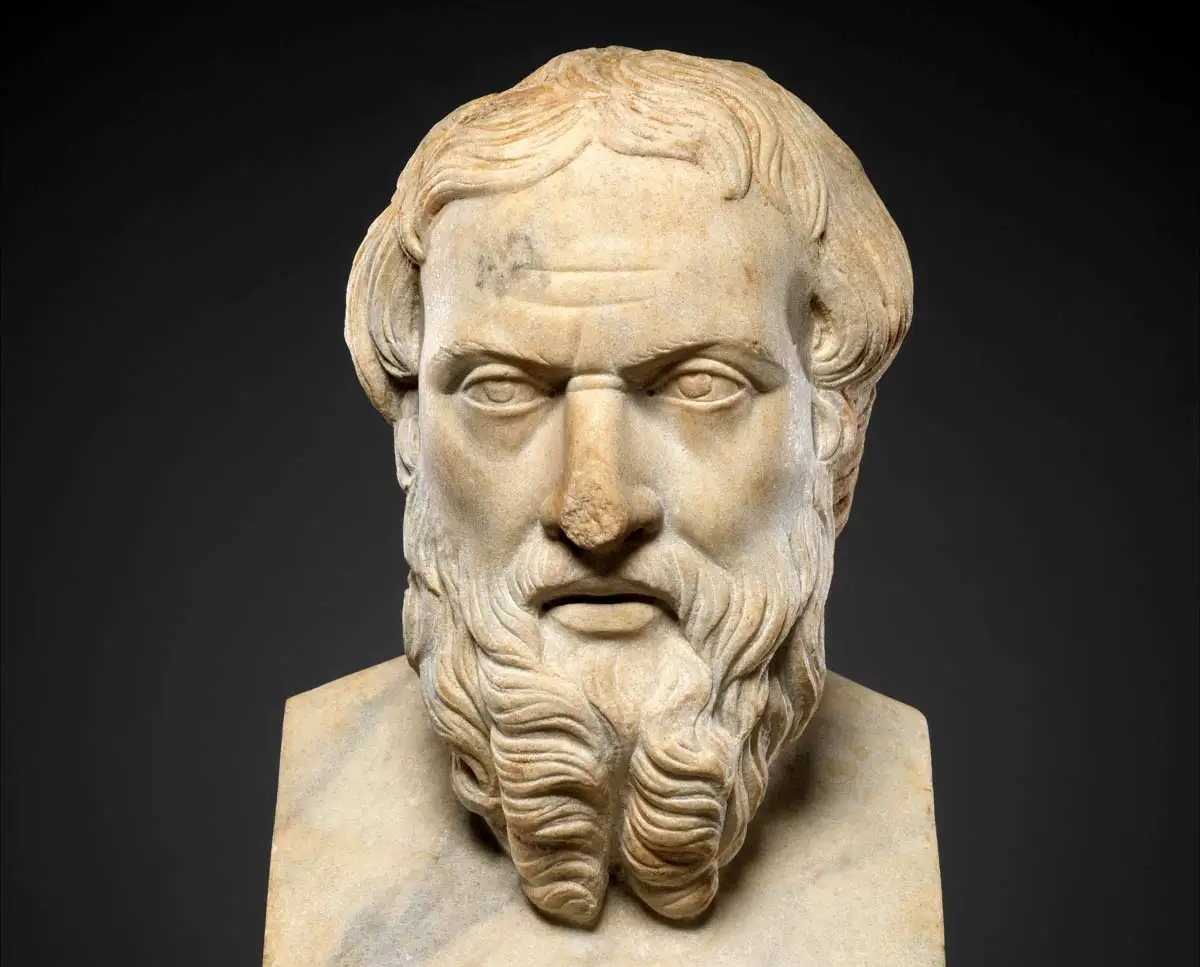

What we remember and what we forget highly depends on the people we have around us, the society in which we live, our social context. French philosopher Maurice Halbwachs called this social function of memory “collective”. However, the understanding that memory is a social endeavor was not invented by Halbwachs. In fact, it goes way back, even as far back as Herodotus, the father of history himself.

Herodotus and Memory

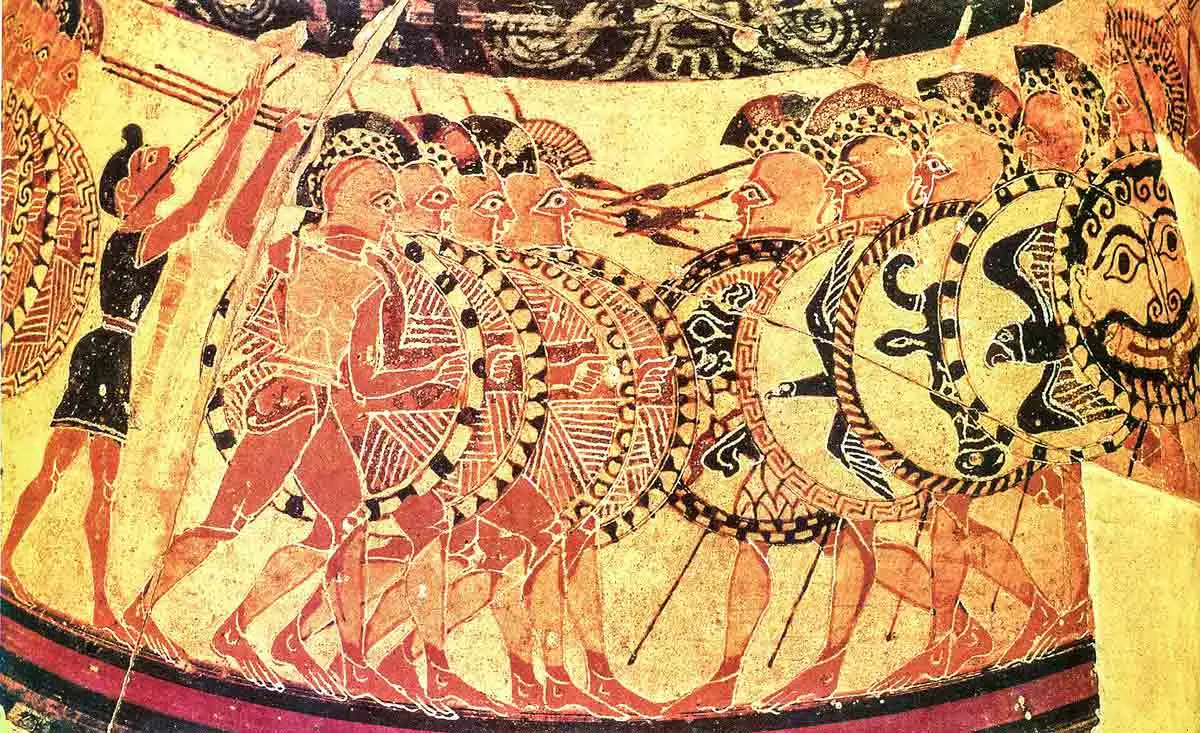

Herodotus of Halicarnassus wrote about the wars between the Greeks and the Persians in his Histories. Writing a few decades after the war, Herodotus did not live during any of the events he described. His work was based on second-hand testimonies some of which more reliable than others. Hiw work is in a sense a recording of the collective memory of the wars as it existed during Herodotus' time.

In the very begining of his Histories, the Greek historian introduces himself and states the purpose of his work:

“to the end that neither the deeds of men may be forgotten by lapse of time, nor the works great and marvellous, which have been produced some by Hellenes and some by Barbarians, may lose their renown; and especially that the causes may be remembered for which these waged war with one another.”

Interestingly, the term memory itself is absent from his introduction but we get an outline of how he understood it as the resistance against the “lapse of time” and “forgetting”.

His stated aim is twofold: preservation and fame (kleos, in the original Greek). Preservation of the past and the good fame (kleos) of certain actions and individuals.

Herodotus was aware that unrecorded memory fades with each consecutive generation. Historians have long observed that oral, unrecorded history is typically lost within three generations. Think of what you know about your family’s whereabouts three generations ago. What were these people’s names and professions? It is highly likely that you cannot answer this question.

When it comes to your parents and grandparents things are far more clear. You most likely know their names and a great deal about what they did for a living. This is what Egyptologist Jan Assmann has termed communicative memory. For Assmann, if groups of humans depended on communicative memory, their stories would be lost within three generations. To that end, civilizations or, more correctly, cultures, develop a cultural memory, a way to preserve important memories of the past through images, text, and ritual.

Spoken Words Fly Away, Written Ones Remain

Texts are powerful mnemonic tools, as writing crystallizes memory in a solid form that can pass down from one generation to the next one. Herodotus understood this. Two hundred years later, oral tales about the Persian Wars would still exist but his written testimony would, by then, have become the standard version of how things happened. His voice would still be heard and in the next section, we will explain why this would be important.

Memory as a Path to Immortality

In the epic poetry of Homer, heroes are very conscious of the way their memory will “live” after their death. This means that they always act with the future in mind, as they want to ensure that their good fame (kleos) will live on.

This desire to be remembered is also accompanied by a fear of being forgotten which was seen sort of like a second death, just as good fame was a man’s claim to immortality.

Herodotus lives within this tradition and his work can be seen as both a way to immortalize the deeds and works of his people and a way to earn himself the right to become immortal by successfully fullfilling the difficult work of recording what happened and also tracing what caused it.

Herodotus is in a sense placing himself next to the heroic deeds he describes in his work. Without him, memory will fade, and forgetting is death. His work at keeping the memories alive can be seen just as heroic as the works he describes, and for this he hopes that his fame will be a good one. And if we judge by his nickname “father of history”, he understood the game very well.

Bibliography

- Assmann, J. 2011. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fragoulaki, M. 2020. Introduction: Collective Memory in Ancient Greek Culture: Concepts, Media, and Sources. Histos, ix-xliv.

- Herodotus. Histories. translated by G. C. Macaulay. Gutenberg Project.